1. CAMPUS

Historical

International

Danish

Finn Junge Jensen, rektor CBS, of

Copenhagen Business School, theme meeting

at the Danish University and Property Agency

Campus areas are places full of life. Foreign students and researchers are drawn there by a vibrant environment. If we want to attract the best foreign capacities, we have to start by focusing on the campus area

Three perspectives

The following articles consider campus planning from three different perspectives. Together they describe what campus areas are and how they have developed.

The historical perspective takes a look at how universities have been built over the last 800 years, based on two traditions. According to one of them, the university is enclosed within itself, whilst in the other tradition, it opens up to the surrounding world and urban life. Although opposites, the traditions also complement each other in a way that is useful for today’s needs for both dynamics and in-depth studies.

The international perspective describes basic historical and cultu-ral differences between American and European campus typology and suggests a way of developing a European campus model.

The Danish perspective tells the story of Danish university planning’s development in recent years. Initially, this was mainly an ad hoc activity, but today we witness more strategic planning with consequences for the surrounding city.

The university and the city – two traditions

By Claes Caldenby, Professor of Architecture at Chalmers, Gothenburg. He has written about universities and university environments. He is the author of the book ‘Universitetet och Staden’ (The University and the City) from 1994.Two different views of science are reflected in the university’s buildings and its physical relation to the city. Science can be considered as driven either by inner forces or by interaction with the surrounding world. This article offers a historical view of the make-up of universities and the movement between the immersion of the university and the city as a dynamic ’outside world’

The university and the city – two traditions

For a long time, intellectual history has worked with two perspectives of the forces behind changes in science. One perspective considers science to be developed by inner driving forces, as contradictions emerge in a solution-finding thought system. This is called the internalist perspective. The other perspective claims that ‘reality’ raises issues and creates the preconditions for the development of science. This is called the externalist perspective. The two perspectives can also be used to describe the physical organisation of universities and their relation to the city. One is more closed and the other is more integrated in the city. The dispute between the two perspectives has at times been quite heated. At the same time, it is widely accepted that the two perspectives complement each other.

In the physical organisation of universities, the internalist perspective is evident in a closed, undisturbed environment of specialised truth-seeking and intellectual discussions at a high level. The externalist perspective deals with the university as strongly involved in the development of society, both in terms of issues addressed and in terms of how knowledge is applied. Therefore, in this perspective the university is also dependent on being an open meeting place for different currents of thought – well integrated in the city.

In the postscript to the book ‘The University and the City’, 1988, editor Thomas Bender writes about the differences and similarities between universities and the city. The city, he believes, is an “open heterogeneity”. The heterogeneity refers to the multiplicity and the inner contradictions inherent in any complex institution. The university is a “semi-cloistered heterogeneity”. The semi-cloisteredness represents a delicate balance between the university’s inner world (the cloister-like closedness) and participation in the exterior context. The interface between the university and its surroundings becomes an important spatial aspect.

Two traditions

Two traditions run through 800 years of university building history: The internalist tradition encompasses the college, the American campus and what might be termed the external university. The externalist tradition includes universitas, the institutional university and the city campus. These traditions are very much alive, both because of buildings that are still in use and because of points of view that are passed on in new buildings. I will alternately describe the internalist and the externalist tradition through a series of examples.

The college

The college was established as a foundation by means of donated funds during the Middle Ages. It had statutes that governed the life of teachers and students. Collegio di Spagna in Bologna dating back to 1367 is often considered the first specialised university building in Europe. It is clearly modelled on the monastery. A closed wall surrounds a square two-storey building around an inner courtyard. Here, teachers and students sleep, eat and study in a world of its own. At one end of the courtyard there is a church, exactly as the church by the cloister.

he tradition lives on in English colleges. At Oxford, college areas are spread all over the city with houses and classrooms around large quadrangles, often with a church at one side. Cambridge is more divided into a row with the college on one side and the city on the other – the contrast known as ‘town and gown’.

Universitas

Universitas means ‘guild’, in this case the guild of university teachers. Early universities were not physically anchored institutions, they could actually move from one city to another with their small collection of books. They did not have any purpose-built rooms, but rented space in ordinary houses in the town. Albeit preferably in one particular part of the city, just as other guilds belonged to their particular streets. The university’s street might be called ‘School Street’, ‘Book Street’ or something similar. In central Copenhagen, it was called ‘Studiestræde’ – Study Alley.

For large gatherings and formal occasions, the local church was used. One important aspect of universitas was that students, just as the teachers, formed their own ‘guilds’, or fraternities, and that they were clearly independent of and partly separate from the college.

The campus university

The campus university is originally an American tradition. The earliest reference to the concept is found in a letter from 1774 about the Princeton university area. The tradition of American universities was brought over by the first English colonialists and had its origin in the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge. In America, there were no towns in the Middle Ages. Furthermore, the universities were often established at ‘the frontier’, as their primary task was to educate priests. It was considered particularly important to carry out missionary work amongst the Indians. There was no basis for encircled courtyards here. The square became a ‘yard’ or a ‘ground’. Following independence, the campus concept spread and ended up denoting not just the lawn in front of the main building, but the entire university area. Part of the college tradition lived on in the idea that the university should take responsibility for the student’s entire life, even including accommodation and spare time, e.g. sports. The university stood ‘in loco parentis’ i.e. in the parents’ place.

The institutional university

The institutional university on the European continent belonged more to the universitas traditition. As the university grew and had more purpose-built buildings – first anatomy theatres and astronomy observatories and then, from the 19th century on, an increasing number of specialised scientific institutions – it was no longer possible to keep the university area in one place. It became necessary to use plots of land that could be acquired around the city, which resulted in a more or less spread-out localisation, well-integrated in the city. In the course of the 19th century, new main buildings for academic ceremonies were constructed in many places. They also became a means of asserting the place of traditional humanities subjects at the university. And the seminar room became humanities’ answer to the laboratory of science.

The external university

The external university became the solution to the educational explosion of the 1960s. These university areas are often called campuses, but contrary to the American tradition, they do not usually include student accommodation nor sports facilities. One similarity is the separation from the city. The exponential growth of the university – a doubling of the number of students in 10 years – made extension possibilities and space for expansion a main requirement. On that background, the universities almost without exception were placed on the outskirts of a city or actually outside the city, surrounded by a lot of open space. The university gained a clear, cohesive identity. Integration into the city deteriorated. They were called ‘education factories’ because of the narrow-minded focus on teaching and speedy throughput.

The city university

The city university became the 1990s’ answer to the criticism against the external university. Once again, integration into the city was emphasised: the city as an approach to the university and the university as an approach to the city. In France, an extensive programme, ‘Université 2000’ was carried out, which aimed at moving the faculties into the city or turning the external universities into more urban environments. In Sweden, all newly established universities from the expansion boom of the 1970s were located either on the edge of or outside the city. During a new expansion wave in the 1990s, all new establishments were placed in available buildings. Often, old industrial facilities or military barracks were taken over. Today, external universities and city universities exist side by side, as buildings, as thought models, as today’s version of the two Middle Age models: the closed college and the well-integrated universitas.

Avenue of knowledge

By 1975, Gothenburg’s large university was spread across more than 70 different addresses in the city. A joint move had never taken place, as had happened in Stockholm. The disadvantages were evident: no economies of scale in terms of anything from cleaning and caretaker to café and library; slow dissemination of information; less spontaneous meetings between teachers from different academic disciplines. But there were some advantages, too: To local politicians, the university no longer appeared to be a world in itself. The ‘free and easy’ atmosphere at the small institutions furthered contact between teachers and students, and made management take on more responsibility.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Gothenburg’s university was gathered in faculties, in clusters, which were given the size of entire city quarters, but which remained spread across the inner city. At the same time, the view of this changed, and the advantages of the city university were considered quite obvious. Over the course of a couple of years during the 1990s, a report was prepared in collaboration between the university, the municipality and the business community, based on the university.

The purpose was to “create a better and more vigorous city”. In customary planning style, the report presented a simplified image of the university in the city. The scattered localisation was summed up as a ‘university ring’. Three ‘avenues’ were added to this image: an ‘avenue of culture and entertainment’ along the city’s main street, Kungsportsavenyn, an ‘avenue of events’ with sports facilities, arena, exhibition hall and amusement park, and a less established ‘avenue of knowledge’ across the river for a new part of the technical university. The problem with this ‘avenue of knowledge’ is, however, that it requires a boat. This kind of planning is much too abstract to capture what I believe to be essential in order to create a living avenue of knowledge at the interface between the buildings and the city. Another picture exists that captures this interface better.

Urban spaces as meeting places

The ethnogeographer Torsten Hägerstrand has described his day as a student in the institutional university city of Lund during the 1930s. Hägerstrand developed ‘time geography’ as a science, and for this he uses trajectories through time and space. He describes his journey through the city from his home to a restaurant to various teaching facilities and the student house: The Academic Association. It illustrates that the way in which to use the city is a continuous movement in and out of buildings. The point is also, that his journey is overlapped by many other people’s journeys, creating opportunities for unexpected encounters. The city is a ‘creative space’, and it consists of real avenues of knowledge. Hägerstrand’s description of a trajectory belonging to a professor of medicine in the 1970s renders a somewhat different image.

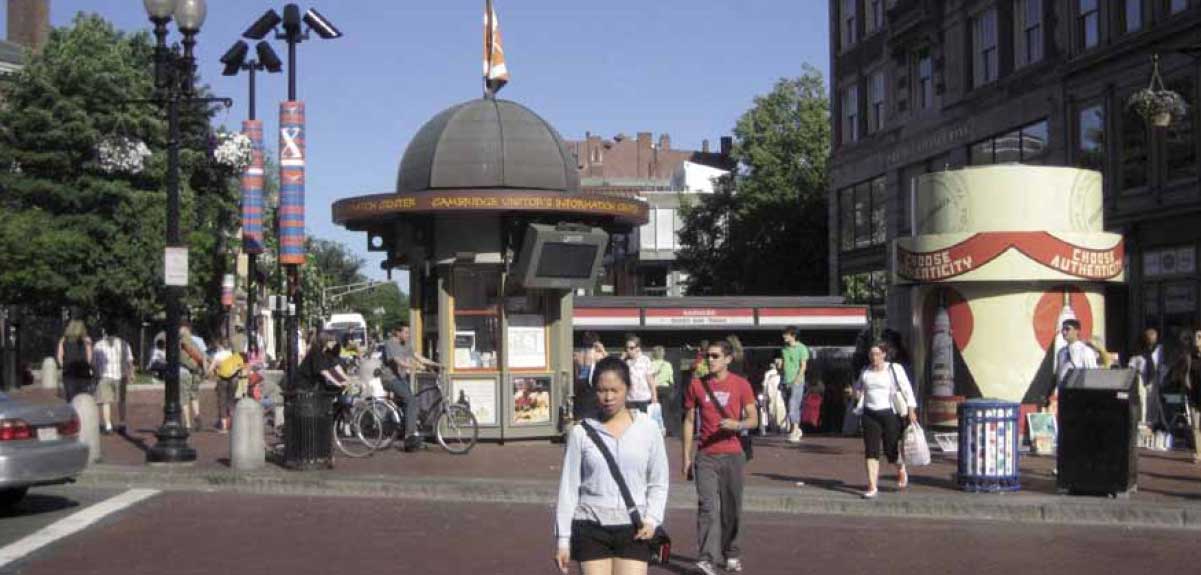

He drives his car from his home outside the city and spends all day in the same specialised environment at the hospital. No unexpected encounters occur. The architect Christopher Alexander’s book, ‘The Oregon Experiment’ from 1975, which deals with the development of a university in Oregon, is characterised by similar thoughts. One of the patterns that he describes is the ‘open university’, which dissolves the boundary between city and university, and allows them to grow into each other. Other patterns include ‘university streets’, where the university is extended in small units along the street, ‘local administration’ in small, scattered units, ‘department hearth’ as rallying points in any institution, directly joined to passages and with all rooms that are important to the institution close-by, and last but not least, ‘real learning in cafés’, which are privately run cafés, restaurants, bookshops and cinemas close to each other, which serve as meeting places for students, teachers and local citizens.

The encounter between city and university

The interface between the university and its surroundings is an important spatial aspect that outlines the framework for creative work. The physical planning must balance between the university’s inner world and participation in society. This article shows that the internalist and externalist perspectives are not incompatible, but that they rather complement each other. Creation of knowledge is a creative work. And the descriptions of Lund and Oregon are based on the idea that creative work is best carried out in continuous commuting between private and public life. Between introverted thought work and extroverted testing of ideas.

Research: Cathrine Schmidt

The future of the European campus

By Martin Wilhelm, architect and partner at mwas, Frankfurt, and Judith Elbe, architect at Technische Universität Darmstadt, have written the book ‘Der Campus – Zur Zukunft deutscher Hochschulräume im internationalen Vergleich’, which compares the European and the American campusThe US campus is admired and many European universities try to copy it. However, it is worth noticing some fundamental cultural and historical differences between the two typologies that have an influence on how the same idea works under opposite conditions on the two continents. This article summarises points from a German research project, which compares a large number of European campus areas with a large number of American ones in order to define what a European campus is and how it is planned.

Princeton and Harvard. To most people who are concerned with the development of the European university, such spectacular institutions appear to represent the very ideal of higher education. Only there is it possible to raise the future elite. Would it not be the most desirable goal to find these shining places, this close academic community, this lively 24-hour-campus in Europe as well?

However, there is a basic misunderstanding about the very idea of ‘campus’ behind the envious views across the Atlantic. The Harvard model does not work in Europe, and the European campus is already alive and yet to be discovered!

Campus: institution, community, space

Educational institutions are intertwined with and dependent upon the society in which they function and for which they have been made.

All universities are comprised of three interdependent parts:

- The institution as education and research departments, employer and representatives;

- The academic community, i.e. students, professors and staff;

- The space of the university, as the habitat of the university members and its built manifestation.

The successful development of the university requires all three parts: institution, academic community and space.

Each university consists of one or more locations housing teaching, research, institutional, administrative and infrastructural facilities. But the university space¹ is much bigger than those locations. It encompasses non-institutional facilities and spaces as well. What belongs to the ‘campus’ is subject to the perception of the community and to the surrounding observers – the city.

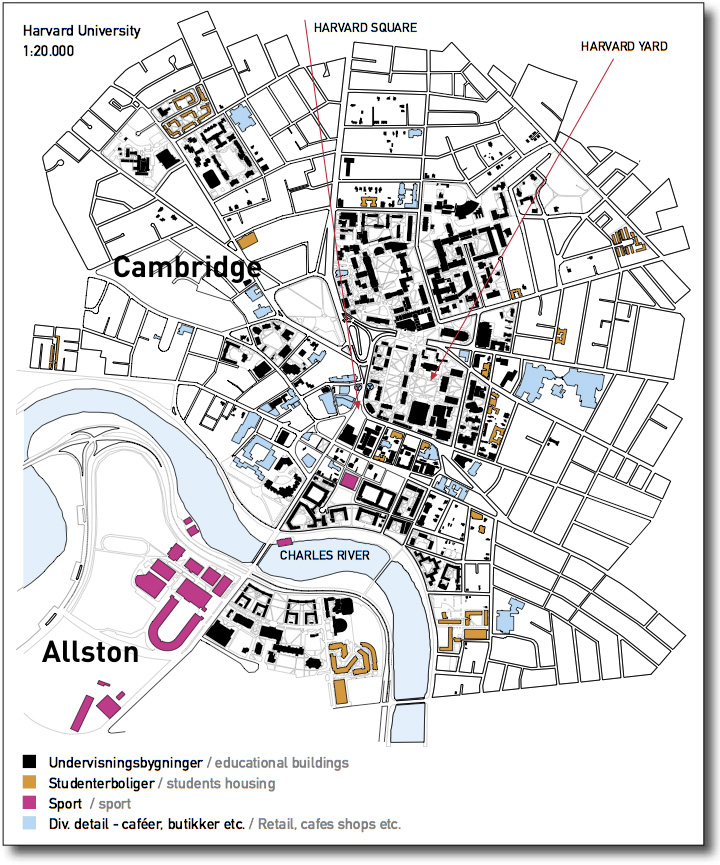

The difference begins here: Harvard is a town within a city. Various locations and spaces of the university overlap. That determines the special character of this campus type. Everything there seems to work perfectly, seductively inviting one to use it as a general blueprint for university development.

In Europe, university spaces and locations do not overlap. Thus, the European campus is another kind of campus, one that requires a rather differentiated search into the culture and identity of the surrounding city/society and in the collective consciousness – in combination with research into the respective university’s history, its institutional organisation and its academic community.

US: campus before city

The founding of the American university was an essential part of the colonisation of a wild country. The first universities were the frontier of civilisation. Through the founding of universities, the religious Pilgrim Fathers attempted to model a better world and an antipode to the Europe of morally rotten cities. Institutions like Harvard, Princeton and Berkeley were there before the surrounding cities. Education always meant civilisation and formation of a better man and society.

ven today, a fear of the city – of the uncontrollable – remains strong, exemplified through the suburbs and gated communities. American urbanisation means suburbs in combination with nodes of densification. The most notable kind of node is the campus. Distinguished from the environs, protected, well maintained and without the need to intermingle with the perilous surroundings. On campus, brilliant urban and landscape design and architecture can be found. This is where the future and the ideal of the American city are realised. Museums, theatres, libraries and collections were founded and remain on campus; research naturally finds its place here. And down the road, universities are home to major sports teams. Fear and monastic idealism have merged to create the American campus, the heart of American urbanisation.

Europe: university in the city

The idea of ‘university’ is a European concept. The development of institutions with a universal approach to knowledge was the expression of a progress-orientated urban community with the need for intense exchange – thus the concept of unity of research and teaching.

European universities show impressive historical importance. Common to their development is that they were founded within existing urban societies and as a part of the surrounding city. They represented the ruling order and contributed to the reputation of the sovereign.

University and city grew with mutual influence. Even today, they are tightly connected through student neighbourhoods and shared institutions. The city offers museums, theatres and public libraries, sports clubs and infrastructure, and the academic community uses them and becomes active in them. The European city and university are unified. While in the US, you study at Harvard (in the city of Cambridge), in Europe you study at the University of Frankfurt.

Institution and identity: mass university versus academic village

The institutional structure of the European university reflects its main purpose: State-run, it is optimised for efficient mass education. With one professor as the core, ‘chairs’ offer specialised teaching and research. Departments are weak bodies, self-governed by the chairs, with the dean as the rotating (approximately every two years) ‘first amongst equals’. The central bureaucracy is strong, administering all funds. In this system, students have to be independent and ‘grown up’. They shop around for the education that best fits their personal study goals. They consider the university as a workplace. Entering the university is the beginning of their professional life.

The typical built structure of the European university is comprised of large inner city complexes combined with post-war satellite areas, designed to accommodate the student masses of the scientific revolution.

Universities have to compete through excellence in their fields but are always in danger of being accused of wasting tax money if spending becomes visible from the outside.

American universities, on the contrary, form academic villages. “But the founders were resolute in the collegiate belief that higher education is fully effective only when students eat, sleep, study, worship and play together in a tight community” (Turner, 1984, p. 23). Thomas Jefferson’s design for the University of Virginia in Charlottesville shows the ‘Professors’ Houses’ surrounding the central campus: Here, professors and students live and work together forming an academic family and village. These ‘villages’ are governed by a strong dean and managed by a central administration.

The built structure of this village is important for carrying its image and ideas. A tradition of buildings by famous designers offers landmarks to the outside world and points of identification for the members of the academic community. The buildings express the spirit and the achievements of the institution.

The housing facilities are one of the most important components of the American campus. Most of the venerable buildings surrounding Harvard yard are undergraduate dorms – a fact that is very surprising to European visitors. Far away from their homes the – in many cases only 17 years old – undergraduates find a surrogate family in the American college system. Living together and socialising while taking responsibility and learning thus form the undergrad curriculum.

he on-campus housing forms the special character and the 24 hour-liveliness of the American campus – a quality that the European campus will never be able to achieve on university locations.

The European campus – innovation starts with trace tracking

Harvard may be brilliant and attractive. However, even though it is more difficult to spot, the European ‘campus’ exists, is alive and is worth further development! It is a space intertwined with the surrounding city, neighbourhoods and their culture and infrastructure. In university cities like Tübingen or Florence, the entire city takes on a ‘light’ university lifestyle and in Munich and Barcelona, the university shapes residential neighbourhoods, a bar scene and cultural activities, and creates an active street life.

Unfortunately, public opinion did not recognise this ‘secret’ until it was endangered. The University of Frankfurt planned to create the ‘Harvard of Europe’ by moving from its embedded location to three remote campus areas. When one visits these newly built places on a Saturday it is notable: closed gates, empty, guarded. This is not a campus but an empty hull, lacking the proper history and background. Now that the students have moved away from the old locations, action groups have formed to ‘save’ the university character of the neighbourhoods.

Harvard as a place does not work in Europe. It rather endangers the variety, the cultural qualities and the special charm of the European university campus.

To further develop this European campus we recommend three main points of action:

- Description of the local particularities of the university and its surrounding city, promotion of its (often times hidden) qualities, thus creating an image.

- Analysis of all the various locations belonging to the university, as well as non-university locations that clearly contribute to the university experience, optimising their infrastructure and improvement of their appearance/functionality.

- The ‘zip’ strategy: intertwining city and university with public spaces, transportation, bicycle paths, continuous signs and landmarks as well as through shared institutions, culture and activities.

Above all, it is important to agree on the general rule: The space of a university is its campus. This space by far exceeds the sum of the locations of the university and is only functional as a whole. Where, as is the case with most European universities, university and city are complexly intertwined it becomes challenging to describe the campus. The European university is not an island in the city; its space overlaps large city neighbourhoods. Campus development thus becomes a matter of collaboration between university and city developers and planners. This collaboration between university and city planners is urgent and essential and mutually beneficial for the development of both the European university and the European city!

NOTES

¹ This definition of ‘campus’ as ‘space’ is based on the relational understanding of space described by Prof. Martina Löw. She understands space as the relational order of social goods and people in a certain place. This perception of space connects the structuring, static and ordering function of space with its genesis and permanent change (Löw 2001).

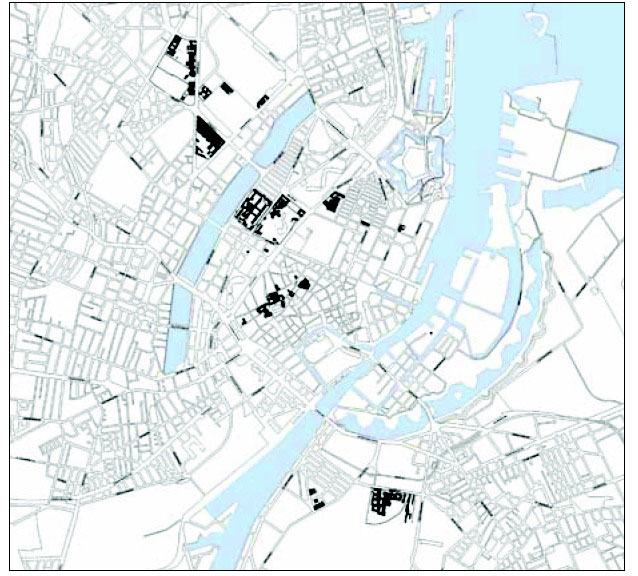

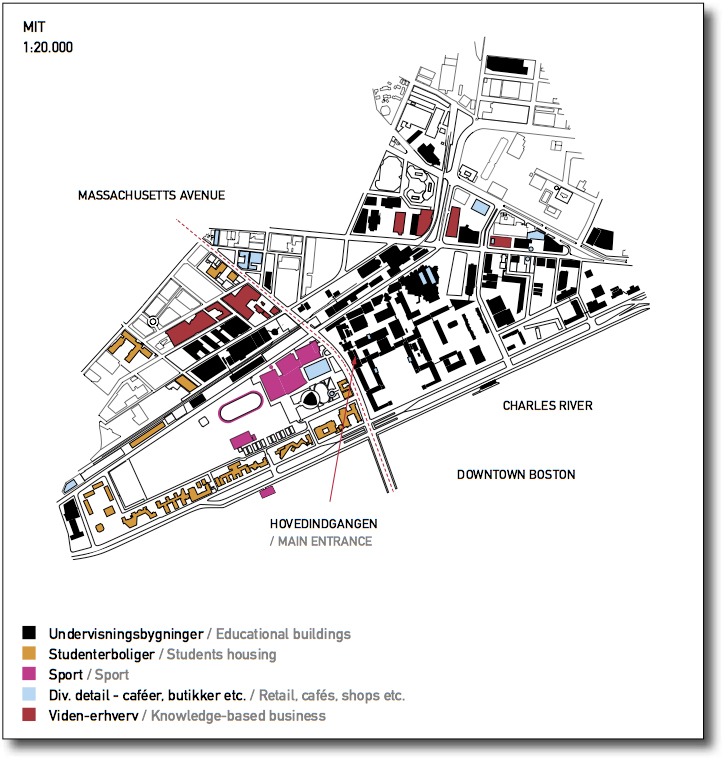

One typical difference between the American and the European campus is that the American has grown step by step in large and medium-sized urban-like building structures, whilst in Europe, we have more often built large teaching complexes in one go. Here, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Princeton University shown on the same scale.Danish university planning – then and now

By Klaus Kofod-Hansen, Chief Planner at the Danish University and Property Agency, who has worked with campus planning for Danish universities for the last 10 years.University planning started in the mid-19th century with the development of modern science. Up until the last decade, planning was characterised by the vision of one compact university located on the city’s edge. From then on, a new development has emerged, in which city and university are developed together

The extension of the Danish university sector via planning follows the expansion of the cities and first saw the light of day around the mid-19th century. Prior to that, university extension was more of an ad hoc activity, based on current needs and the few available plots of land in medieval towns. To a great extent, the university sector’s expansion follows the development of modern science. Old buildings were not adequate for housing the new functions.

University planning in Denmark started with the University of Copenhagen. In contrast to other European city universities, it was decided to move parts of the University of Copenhagen out to released areas by Rosenborg Bastion. The Botanical Garden was established here, as were the Observatory and a number of other university buildings close to the Municipal Hospital.

Then followed the relocation of the Veterinary College from Christianshavn in 1856 to the open country at Frederiksberg. The school which is today known as The Faculty of Life Sciences was established in the manor-like building designed by the Danish architect Bindesbøll. At the same time, the College of Advanced Technology (now Denmark’s Technical University) was established on open embankment areas by Sølvtorvet square.

The establishment of Aarhus University at the beginning of the 1920s would become a significant manifestation of how universities were moved out into the provinces. The government wanted to improve educational possibilities in the provinces by means of a university in Jutland. In contrast to the universities in Copenhagen, the new university was to offer a world with accommodation, teaching and social life all in one place. In other words, a classical campus plan following the Anglo-Saxon model:

“One very important means to giving character to the university is (...) that the new university to as great extent as possible becomes a college university, i.e. that the university not only offers students teaching, but also has at its disposition student hostels where the students can live.”

“The university complex should, as a whole, be better than that of the University of Copenhagen, though beautiful and with an open landscape. The students’ physical and personal well-being should be catered for, not only by means of the student hostels, but also by means of facilities for feeding the students, sports fields etc.”¹

The universities’ development on the edge of the city continues up through the 1940s. The College of Advanced Technology, now located at the centre of the city due to the expansion of the city, tries to expand at this stage. However, a new building complex in the city centre immediately proves too small. Consequently, the Ministry of Education plans for the university to be moved outside Copenhagen. This happens in the course of the 1960s, when they move to an open area in the town of Lyngby, with good parking facilities, as it is expected that the students will primarily drive to the university by car!

The 1960s saw a significant growth, both in the number of students and in the demand for academic labour. The government decided to build a third university in Denmark. Odense University, today known as the University of Southern Denmark, was designated as a supplement to Copenhagen and Aarhus.

And suddenly, development took off. Even before Odense University had been established, the Danish Parliament decided that it would not be sufficient to absorb the expected rapid growth in student intake. As a result, it was decided as a part of national planning to strengthen business development regionally by establishing two, maybe three further universities across the country.

The new universities were placed outside city centres, as this was the only place a sufficiently large compact area could be acquired. Aalborg was designated as the location for one of the universities. Roskilde was named as the other, as this would best relieve the pressure on the University of Copenhagen.

The universities were planned without residence halls, as the idea that students should spend both their study time and their spare time in the same place was losing support. It was now considered important that students participated actively in society, and that they should be integrated in ordinary housing rather than in residence halls on campus. The Danish Act on Residence Hall Construction was repealed, and instead, priority was given to youth residences for all youngsters in process of training.

Growing desire for city integration

Out of the three new university areas that were planned from the 1970s, Odense University was the first to be built. 4 km from the city centre, without residences or any other functions close to the university. From then on, a growing desire for city integration became evident. Roskilde University was designed to be surrounded by residences and businesses, but with a clear division between the individual functions. Later on, Aalborg University was designed as a city-integrated university in a new suburb. The university was built in enclaves with the largest possible interface to other functions. However, today it is evident that the original intentions about creating an urban context in these three cases only succeeded to a limited extent.

At the same time, space for the inner city faculties at the University of Copenhagen became so cramped that the Faculty of Humanities was temporarily moved to the island of Amager – known today as KUA. Many people think incorrectly that the buildings were constructed for temporary use. They were, however, constructed as normal buildings, but with a general purpose so that they could later be used for other purposes, should the university at a later stage be gathered outside Copenhagen, as plans had it.

Growing universities

The number of students continued to grow. As a consequence, in the mid-1990s, the Danish Parliament drew up a new plan of action for the universities, called ‘Growing Universities’. It marked the beginning of large extensions in the university area and implied the allocation of DKK 500 million annually for new construction over a 10-year period.

In that connection, KUA was extended and modernised, and its location was made permanent. The plans for the future Øre-stad district had all of a sudden turned the university complex into a part of an entirely new quarter of the city, with direct metro access. The new district would house a significant amount of buildings, including the DR-byen (the national broadcasting corporation’s headquarters) and the IT University as neighbours and good opportunities for synergy. The decision to retain the University of Copenhagen, Amager (KUA), meant that the plans to move the university out of the city were finally abandoned. The idea of gathering the university in one place was abandoned, too. This idea was, however, followed through in other places as the opportunity arose.

Copenhagen Business School had been very spread out, but it was joined together in a section of the Frederiksberg district between two new metro stations. Similarly, the artistic educational programmes in Copenhagen were gathered on the island of Holmen in a former military area centrally located in the city. The development of the area also included construction of residential areas and the Copenhagen Opera House.

Aarhus University was kept together, particularly because the government managed to acquire large building complexes in the vicinity, and because the Aarhus University Foundation Construction Company purchased areas and buildings for innovation and IT in the Katrinebjerg neighbourhood close to the University Park. Plans about moving Aalborg University out of the city were finally abandoned.

Rent arrangement

Up until the year 2000, all university buildings were placed at the universities’ disposition by the government on the basis of needs analyses. In 2000, most of the universities were brought under the SEA scheme (the Governmental Property Administration), according to which the Danish University and Property Agency serves as property owner and property letter in relation to the universities. The universities receive governmental grants for payment of their rent, but they are free to manage the properties. The SEA scheme provides an incentive to utilise and rationalise the use of the area and the opportunities for construction according to need. Savings on area rationalisation can be put to use in research and education.

Mergers

Recent years have also seen a significant organisational concentration of the universities in order to accommodate internationalisation and increasing international competition. In 2005, the government initiated a development process within the universities and the governmental sector research institutions. This has led to a series of mergers, reducing the number of universities in Denmark from 12 to 8, whilst the number of sector research institutions has been reduced from 13 to 3. In the coming years, the organisational concentration will be followed by a physical concentration, whereby university facilities will be gathered in fewer locations.

New challenges

One significant challenge in university planning over the coming years will be to ensure expansion options for the universities – particularly in urban settings.

The global challenge within research and education has led the government to allocate more funds for publicly financed research. This will result in the construction of more buildings in years to come, not least laboratory facilities. The laboratories that were built 30-40 years ago are ready for modernisation. The laboratories account for some 800,000 m2, or approx. 40 % of the total university areas. Out of these, only about 200,000 m2, are new or newly renovated (built/renovated within the last 10 years).

Given the increase in research funds and the mergers, several of the universities face new and extensive challenges to create space for future growth. Especially because other university related functions must be added to the university areas, so that they will appear as attractive academic city quarters.

New plans

From the 1990s and onwards there has been great pressure to move the universities towards the city centre, as experience shows that it is difficult to create life on the edge of the city. But space in the city is cramped, and both Aarhus University and the University of Copenhagen have limited expansion options within their own area boundaries. Consequently, the universities, the government and the municipalities are now making plans for future development. The planning involves the municipalities to a higher degree than previously, because their goodwill is necessary when the universities acquire plots of land and make plans outside their own areas in the urban environment.

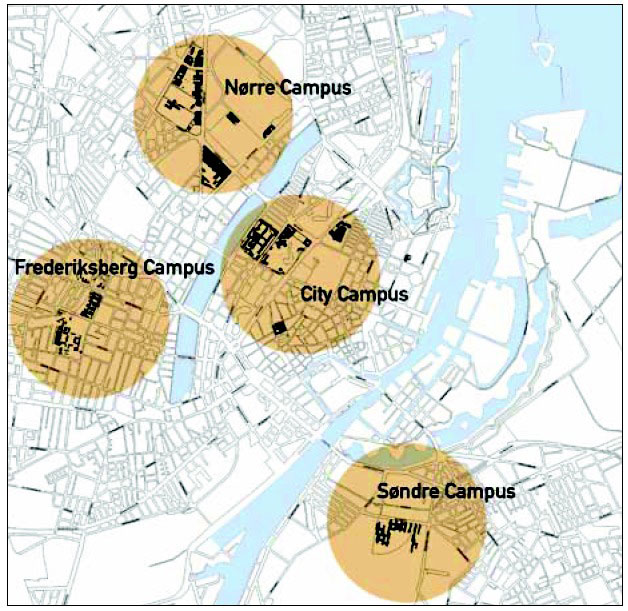

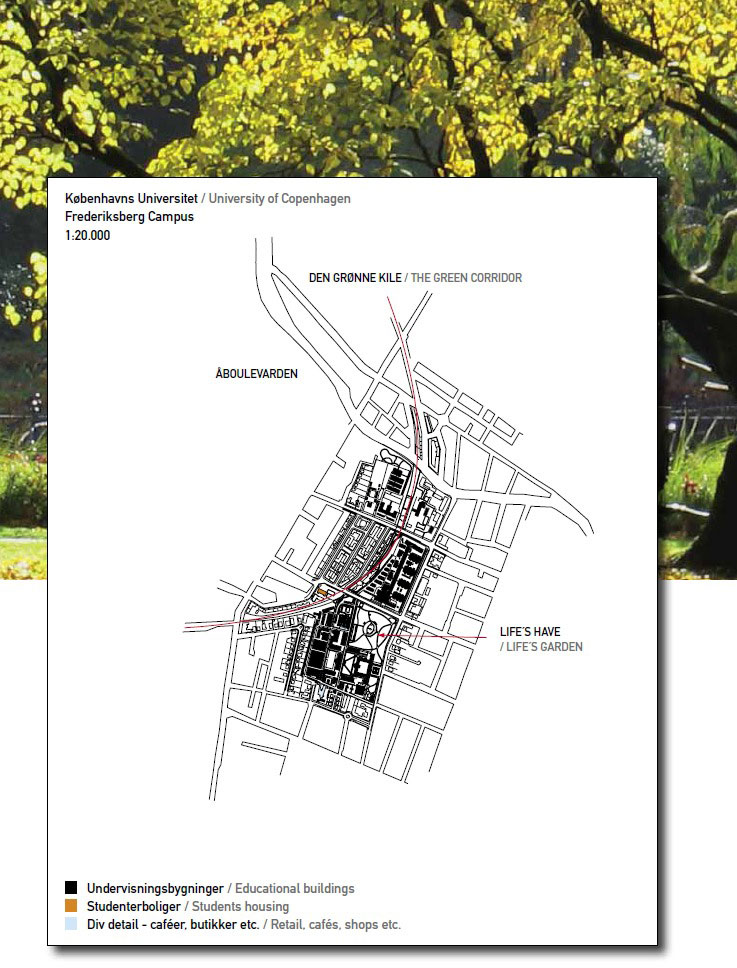

One of the results is a new campus plan for the University of Copenhagen, which concentrates four campus areas in city quarters: South Campus, City Campus, North Campus and Frederiksberg Campus. The division into campuses is based on academic subjects, i.e. each campus accommodates educational programmes at all levels as well as research within a general subject field. The University of Southern Denmark has chosen the same model for its campuses, which are located in the towns of Odense, Sønderborg, Kolding and Esbjerg.

Similarly, Aarhus University has just prepared its visionary plan for the next 20 years, placing a further 300,000 m2 in the urban area around the existing University Park in Aarhus. The intention is to gather all bachelor programmes here, whilst the graduate programmes, PhD programmes and research will be located in the University Park and at 15 research units spread in urban communities around Denmark.

The government and the universities are currently attempting to create attractive campus environments throughout the country. They should both contain the environment and facilities of the city and at the same time offer the qualities inherent in an academic campus. This means a high concentration of academic facilities, innovation facilities, residences for visiting lecturers and exchange students in urban environments – and this will require a lot of space.

The first challenge will be to create a medical and scientific city quarter in the northern part of Nørrebro in Copenhagen, an already completely built-up area.

NOTES

¹ C. F. Møller, The Buildings of Aarhus University), 1978

Strategy

This section poses the question of how to create a world-class campus. It is illustrated by means of examples from a series of studies of Danish and international campus areas carried out by the Danish University and Property Agency under the auspices of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation.

The section provides numerous examples of universities that use the physical framework strategically in order to become even more attractive and functional. They physically open up to the surrounding world and gain a physical presence and identity in the cityscape, whilst at the same time involving the municipality and local environment in sustainable planning. Additionally, the examples demonstrate how functionalities beyond the mere academic ones – such as innovation environment and accommodation for international students and researchers – strengthen the university.

The section as a whole outlines the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation´s view of the physical qualities and functionalities that a world-class campus should contain.

How do we create a world-class campus?

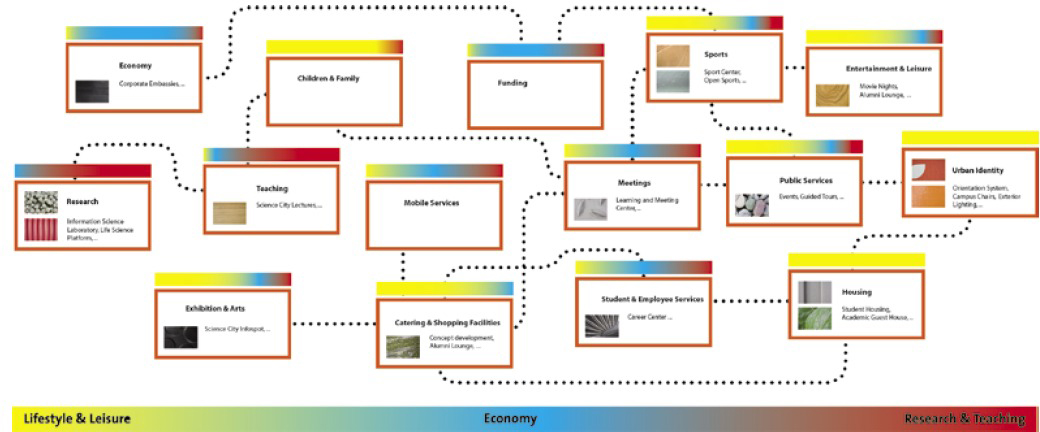

Which qualities and functionalities does such a campus have? And how is it designed and organised physically? The Danish University and Property Agency under the Ministry of Science has carried out a series of studies of Danish and international campus areas in order to shed light on these questions. The result is a series of inspiring examples of universities that use the physical framework strategically in order to become even more attractive and functional. They combine to provide six snapshot images of what a world-class campus should contain, and how it is planned and run

From mono-functional university area to academic city quarter

Modern-day universities have a physical presence and identity in the urban landscape. The studies show that many European universities, which are typically planned as mono-functional zones with a focus on academic activities, are now opening up their areas to the surrounding world.

The typical European campus is built outside the city centre without integrated functions for other purposes than the university’s teaching and research. It often consists of large cohesive building complexes, which have been built in one go or just a few stages. The buildings are functionally designed solely for teaching and research in the daytime. For this reason, residences shops, sports facilities and child care centres are not normally included in the structure.

This type of university can be seen in many places around Denmark, e.g. Roskilde University or the University of Southern Denmark. Earlier complexes such as Aarhus and the North Campus in Copenhagen follow the same model, although today they are located centrally in an urban area. However, at the time when Aarhus University and North Campus were established, they too were located outside the city centres. They were also constructed as large uniform mono-functional building masses.

Currently, there are many Danish and international examples of attempts at physically opening up these enclaves of university buildings in order to create a multi-functional and academic quarter. This is illustrated by the five campus cases described in this book. The purpose in each of the cases is to inspire students to spend more time on campus and at the same time open up campus so that it also physically invites the surrounding community to take part in knowledge, experiences and learning.

This tendency should be seen in the light of the fact that many universities until recent years were obliged to supply two services, i.e. education and research, to society in turn for the funds placed at their disposal by the government. A more recent requirement to many universities, including those in Denmark, is that now they also have to ensure knowledge dissemination. The obligation to communicate knowledge is evident in the planning. It is essential that the universities open up physically to the surrounding world in order to communicate and also to justify their existence.

To several universities, the ambition is to become a bustling city quarter, open 24 hours a day, and with activities late in the evenings. However, reality shows that in practice there is no basis for achieving this in the short term.

As an example, ETH Zürich now works strategically to extend the period with activities at the university by focusing on the weekend. There is no teaching during the weekend, and consequently everything is normally closed; however, during the weekends, the locals have the time and inclination to visit the campus. So, ETH now arranges academic activities, including tours of the laboratories, a children’s chess club and ScienceTalk with well-known researchers. And all this goes on during the weekend. Everything takes place in a purpose-designed exhibition building located centrally and visibly on the campus.

Naturally, the many visitors have resulted in a need for cafés that are open during the weekends, and thus it has started a positive spiral: The cafés and the visitors make it more appealing to the students to visit the university during the weekend, and ETH has seen an increasing number of students who go and work on campus during the weekend.

The studies solely show examples of universities that would like to be considered places that can be entered and visited. Even American elite universities strive for this openness. It is generally considered a means to spreading knowledge and creating greater understanding and visibility, indirectly justifying the existence of the university.

Some establish physical exhibition buildings in the centre in order to reach an audience that would otherwise never visit the university. The reputable architecture and art school Pratts in Brooklyn, NY, for instance, presents its students’ work in its own exhibition building, which is located centrally in Manhattan, where many people have the opportunity to stop by.

The University of Manchester has set up information hoardings along major roads, announcing today’s public lectures and other events on campus. They indicate time and place and encourage participation. These are initiatives that make it easy for outsiders to spontaneously visit the university. New York University is another example of this. It is located as an integrated part of urban life on Manhattan and has lectures in what resembles shop premises. Anybody can follow a lecture and even enter and participate, and in that way, the university’s work becomes more relevant in a very direct sense.

As mentioned in the opening articles, American campus areas, which have a tradition of closing themselves against the surroundings in practice, are now in several places working on physically opening gates and creating opportunities for insight and enlightenment. This is currently happening at Columbia University, which in its ‘Manhattan Village Project’ rents out shop premises on the ground floor to businesses that are related to the university. This means, that a public medical practice for brain examinations may move into the very house in which the university’s brain researchers are teaching and researching etc.

In Denmark, the University of Copenhagen’s North Campus is currently planning an international competition about a holistic plan, which will open up the areas and create greater interplay with the surrounding city. The university’s Faculties of Science and Health Sciences would like to develop the city quarter under the theme ‘Health and Knowledge’ in collaboration with the Rigshospitalet hospital, the Municipality and the Parken national stadium. Today, the area appears fragmented and in parts not very accessible because of very busy roads. The University of Copenhagen wishes to use the knowledge and activity generated in and around the campus to develop the neighbourhood physically and mentally.

The universities’ activities can also be communicated via art. The University of Copenhagen’s Frederiksberg Campus and the Holmen Campus for the artistic educational programmes in Copenhagen have just finished the preparation of art plans that integrate art on campus. The art plans describe a joint idea for the role of art within the campus area and aims at communicating and making professional competencies visible. The work of art also gives the public a reason for visiting campus.

The universities are met by demands for greater openness and relevance to the surrounding world. Naturally, this places new demands on building functions and on campus itself, and it makes it necessary to view university planning on an even larger scale than before.

One tangible challenge when turning mono-functional campus areas multi-functional is that nowadays, universities often do not have the authority to house functions that go beyond actual university functions. This is a tradition that is also seen in other parts of Europe. It is necessary to work on making it possible to integrate kindergartens, residential areas or shops on campus. At any rate, contemporary physical campus planning must be worked out in interplay with the surrounding city as well as its functions and users. A larger and more complex scale than before.

Physical planning used as a strategic tool

Modern universities have a written strategy and policy for the physical study environment and campus. And they act accordingly. The study shows that students and staff experience the study environment at the universities that have clearly phrased a strategy and policy for the physical campus environment as more attractive than those universities that do not have a strategy. Most often, the strategy is an expression of the management’s support and recognition of physical planning as a part of a management toolbox.

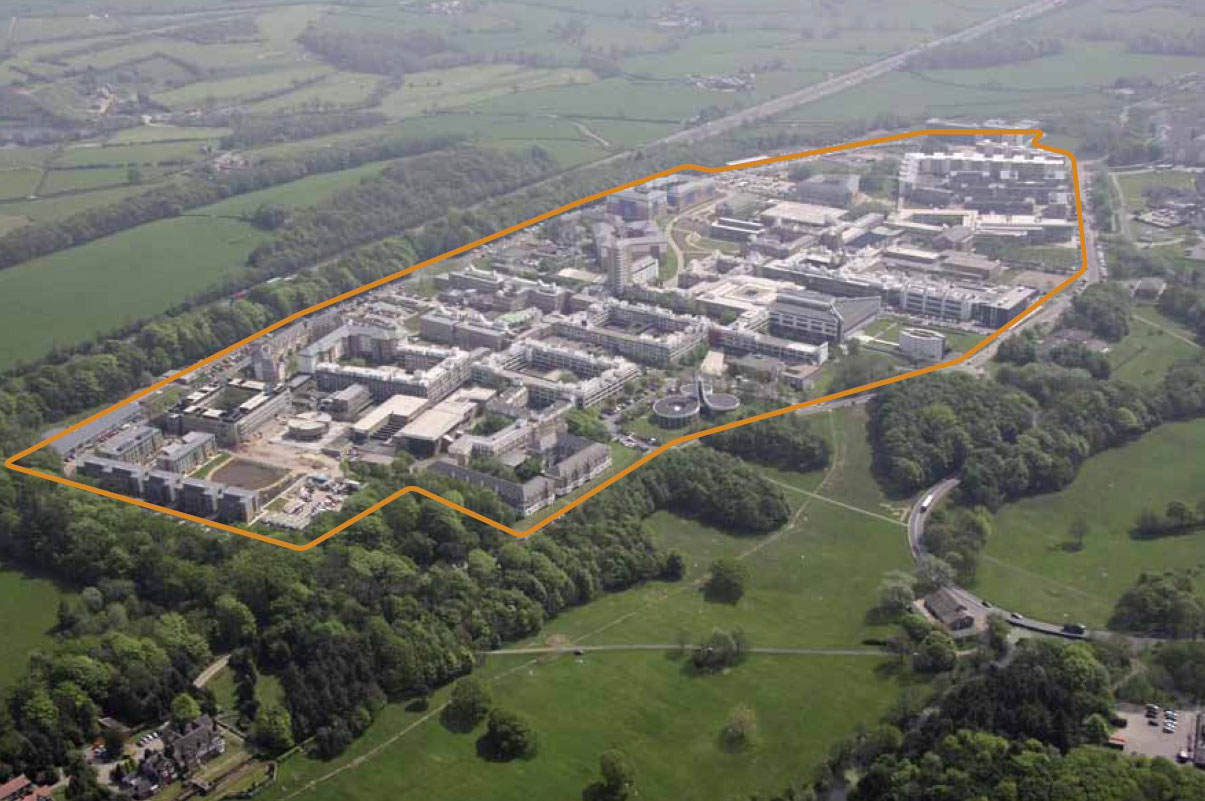

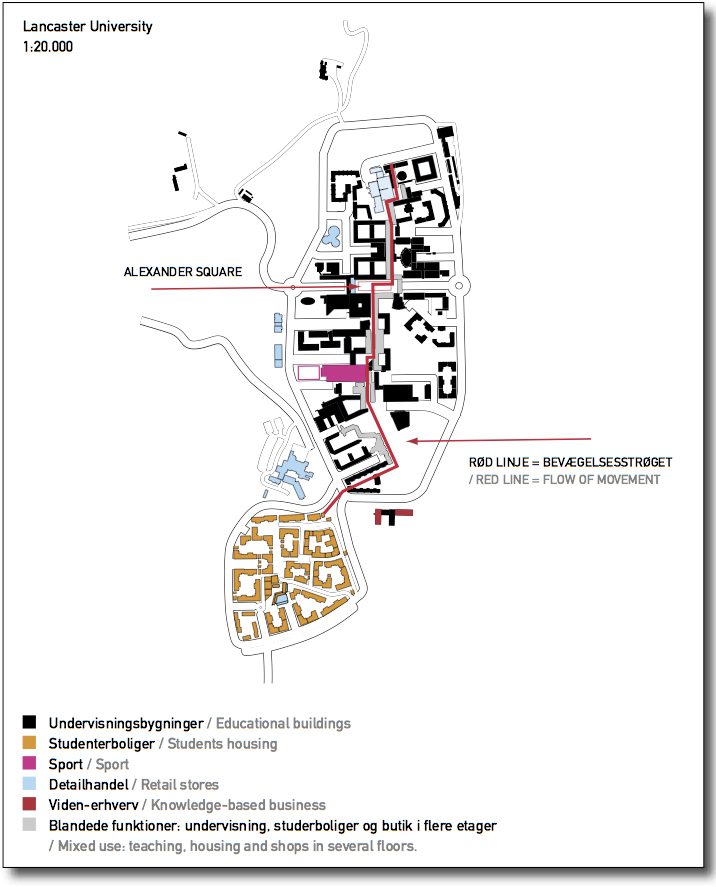

Lancaster University is situated outside large city areas and therefore it has to make a special effort to attract students. A couple of years ago, the university decided to invest in a programme for significant upgrading of the building mass. The university has risen considerably in British university rankings for its good study environment, and today, its marketing focuses on an appealing social environment supported by a good physical framework for both study and accommodation on campus.

Several universities have acknowledged that it takes extra manpower to convert physical strategies into action. In many cases, the strategy cannot simply be implemented as an extra task in the everyday building service. Competences completely different to those normally available in the service department may be required. At ETH Zürich, for instance, a group has been established to ensure and manage the implementation of a large master plan. The group includes both a researcher with a background in physics and a communication consultant.

CBS in Denmark has written a strategy for the physical conditions, and at the same time, CBS uses design as a strategic tool for campus upgrading. According to CBS, they spend a tad more on design and planning because they recognise its significance.1 This focus is clearly noticeable when you visit the Frederiksberg Campus, which appears inviting and modern, in keeping with the signal CBS wishes to send.

Inspiration may be found in e.g. the way in which the Ørestad Nord Gruppen2 uses physical planning in the strategic development of an area in Copenhagen. This is an interest group whose secretariat arranges large and small activities around the city area, which also includes the University of Copenhagen. Ørestad Nord Gruppen targets local residents as well as private and public companies in the new city district. The group counts on both architecture and communication capacities and experiments with e.g. how to utilise temporary city spaces or how to set up sports and spare time activities.

To several universities in the study, the challenge seems to be that physical planning – as in many other types of organisation – is not generally considered and accepted as a development tool, although focus on this is increasing. This also means that funds are not always allocated for the implementation of the strategies. It takes resources and manpower to create and realise a holistic plan.

This is evident both on a large scale, as in the ETH example, and on a small scale. At some Danish universities, managers or employees with a background in architecture serve as alert, aesthetic eyes. They move around campus and take responsibility for ensuring that e.g. interior design, lighting and signposting work as intended. Their presence also ensures that the ideas behind great strategies are communicated professionally to the users.

Inclusion of municipality and local environment in the planning process

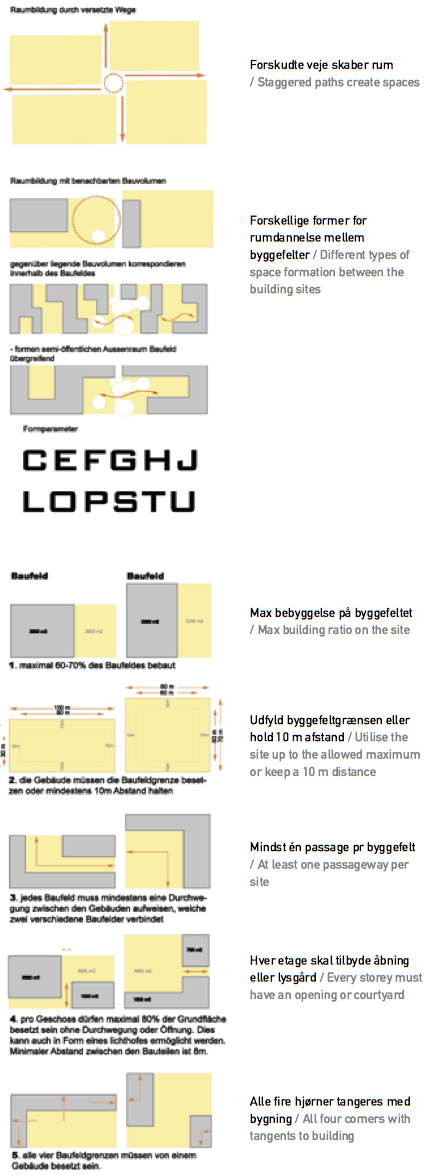

The modern university is in close dialogue with its surroundings. It needs the support and goodwill of the local community to complete its plans. Studies show that the planning process is changing. Formerly, it was common to prepare master plans that indicated possible construction fields, heights and building volume for the coming maybe 20 or 30 years. This made it possible to incorporate the master plan into the municipality’s district plan once and for all.

Today, however, master plans are often replaced by holistic or visionary plans with less specific frameworks such as guidelines, and with a shorter lifespan, e.g. 10-15 years. This combination of a gradual change in the planning method and a shorter time limit means that more and more often, universities may need to request changes to e.g. the municipalities’ district plans in order to complete their building works. This requires a continual and constructive dialogue between the universities and the authorities. Naturally, this does not just apply to a local level, as university planning to a higher degree should also be considered at a regional and a national level in order to ensure a holistic cohesion. Traffic planning is a good example of this. The establishment of a new metro ring is thought of in connection with campus planning, so that it will not only serve residential areas but also large university areas.

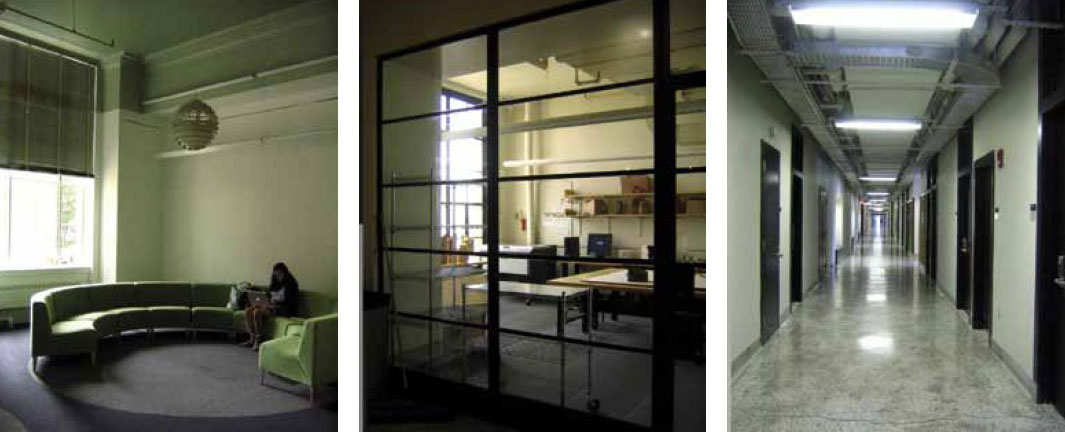

The campus cases in this book represent different planning pro-cesses and ways of involving interested parties. MIT, for instance, applies a model they call ‘Real-Time Planning’, which is an ad hoc planning process, in which the outlook is a maximum of five years. The focus is more on reductions and individual buildings than on large perspectives, such as a general improvement of outdoor spaces. The weakness of this method is that it fails to create unity and cohesive experiences between the individual buildings. This is evident at MIT, where the gap between the houses – from a Danish point of view – is poorly utilised, and only a few places invite you to spend any time there. MIT is known for using world famous architects through the years to design building works full of identity, but the buildings appear as individual lighthouses rather than as a harmonious whole. The real-time planning method’s focus on the individual building does, however, fit in well with the American funding form, which is based on sponsorships. If a sponsor spontaneously offers to finance a specific building, e.g. a swimming pool or a new laboratory, the method makes it easy to quickly integrate new building projects.

Another example is ETH in Zürich, which chose to involve inte-rested parties a mere three months after they had the first idea for a comprehensive transformation of their campus. They prepared a draft to visualise the idea of a dense campus area and used this to enter into dialogue with people and organisations who might have a political or financial interest in the project. The dialogue created the foundation for a master plan competition, which provided guidelines for construction within specific building fields in the future. This process had the advantage that the university, without making large investments, could quickly enter into a dialogue and ensure financial and political backing to realise their vision.

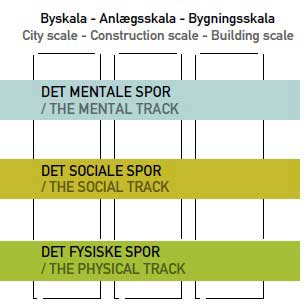

A third model is used by the University of Copenhagen’s Frederiksberg Campus. Through a one-year vision process, they have established the basis for realising a step-by-step extension of the campus. The process has examined three sides of campus at three different levels. A sort of matrix process, in which the focus was to create an overview of and a hierarchy between the various interested parties’ information about and visions for the place. The intention was to establish approved guidelines for further development. The advantage of the process is that it makes it possible to include a lot of knowledge and involve a lot of partners at different levels, all at once.

So far, many campus areas in Denmark have had holistic plans elaborated, which in great detail indicated construction fields and heights for buildings that might not be built within the next 10 years. As can be seen, the content of a ‘strategic holistic plan’ is currently undergoing change. The examples show how universities to a higher degree require frameworks and rules according to which future buildings can be designed. Regardless of the choice of process model, they all require a close dialogue with the municipality and local partners.

The universities also see themselves in a new light in relation to the surroundings. It is no longer sufficient to phrase what they can do for students, researchers and business community. The universities now also articulate to a higher degree how they can contribute to the city or the area. Universities should be an important component in a knowledge city.

This is a new self-understanding, and it requires collaboration with local authorities and players. The University of Copenhagen, for instance, is currently working on developing the North Campus between the districts of Nørrebro and Østerbro in Copenhagen. The intention is to physically open up campus so that it interacts with the surrounding city quarters. To the University of Copenhagen, this means that in collaboration with the Municipality of Copenhagen, building owners and a number of large institutions and businesses in the area, they are currently establishing the basis for a joint vision plan for the district.

It is a challenge to ensure the goodwill and attention of local politicians and civil servants. Many municipalities are preoccupied with how the residential areas develop, and they are not necessarily interested in the needs of knowledge-heavy businesses and educational programmes. Alsion, the knowledge and cultural centre of the University of Southern Denmark in South Jutland encompasses a university, a research park, a foundation-funded concert hall for the local symphony orchestra and a ticket office for Danish Rail in one large building. This is a good example of a type of planning that could not take place without close collaboration with authorities and other partners. The university develops best physically if the municipality and local environment perceive a strategic advantage in the presence of the university.

Opportunity to act on changing needs for e.g. incubator environments

The modern university needs opportunities for quick reaction to changing circumstances. In brief, there needs to be space for enrolment of more students, new research units, start-up projects etc. Studies from other countries show that facilities such as science centres, student centres, parks or incubator environments for young researchers contribute positively to a holistic campus area. They create opportunities for e.g. coupling study jobs and practical assignments closer to the teaching, thereby easing the transition from study life to work life. It is essential to be able to create space for such environments on campus in the future.

At MIT, private research companies have settled in the university’s periphery in areas owned by MIT. The university deliberately invests in areas around the campus area. Partly in order to invest with a view to profit, partly to secure the area for future expansions. It also gives the university the opportunity to build buildings for spin-offs, incubator environments and private companies with which they want to collaborate.

Lancaster University is a public university financed partly by the British government and partly by the university’s own income. The university owns buildings and the land on which it stands and rents out some of the buildings to private businessmen. Lancaster has 6,000 resident students on campus and needs many grocery stores because of its isolated location. One of the tasks of the university’s property manager is to control retail trade on campus, so that retail, residential and teaching areas supplement each other in terms of needs and contents. Among other things he sets up commercially run cafés, which are converted into non-profit student-run places at night, or he offers a cheap rent to a Red Cross charity shop, because it ensures that students donate their furniture and other items instead of dumping them as rubbish, which the university then has to clear away by the end of term. To Lancaster University, the flexibility is not found in their being property owners. They consider this to be of minor significance. Instead, the possibility of renting out to others and thereby creating a profit is of primary significance.

Danish universities are subject to a rent scheme, which implies that governmental institutions within e.g. the research and teaching field pay rent for the buildings they use, most of which are let by the Danish University and Property Agency. This gives the universities flexibility, as they can terminate a lease at short notice, if they do not need it or require it for expansion.

Aarhus University additionally collaborates with a property company under the auspices of the Aarhus University Research Foundation. The company constructs buildings and then lets them out, primarily to the university. The property company has been an active player in the extension of computer scientific learning and research environments at the Katrinebjerg area, which were bought and developed by the company. The property company lets out areas to both businesses and Aarhus University. Consequently, several subjects within the institute of computer science today coexist side by side with private consultancies from the IT sector.

When it comes to being able to act quickly to changing area and functional needs on campus, the challenge is an increased risk and financial uncertainty. For instance, it may be difficult for universities to be bound to an area which they are not sure that they will be able to let out, e.g. to small newly started businesses. The physical presence creates synergy and is decisive when a university expands. It may mean increased focus on the existence of e.g. cheap and flexible areas with low operating costs.

Strategic use of accommodation for foreign visitors

The modern university not only offers attractive learning and research environments, but also attractive accommodation options for its foreign visitors. The studies indicate that several universities, also Danish ones, consider the number of foreign visitors on campus as directly proportional to the number of attractive residences for foreign researchers and students. The residences are a significant key in a strategic effort to establish an international study and research environment. Residences also ensure life on campus and are therefore included as an urban development factor for the campus.

Foreign universities work with residences on campus to a much higher degree than Danish universities. American and Anglo-Saxon universities in particular consider housing options along with the educational programme, but universities from the European mainland are also interested in integrating housing on or around campus.

There are historical and cultural reasons why Danish/European students and researchers primarily live outside campus, as Wilhelm and Elbe describe in their article. A typical Danish campus – in contrast to an American – is built as a place of work, and it is situated as a supplement to the city, just as business areas are. This explains why housing, shopping facilities and varied cultural spare time offers for young people are not a natural feature around campus as it is seen in the USA. In Denmark, we also have a cultural desire to make young people independent, including by giving them a life where they are physically away from studies and teaching. Similarly, it is traditional that researchers and teachers do not spend their spare time at the university, but instead participate in social life and make use of the cultural offers outside the university. In spite of these fundamental differences it is, however, worth noticing a couple of housing initiatives abroad, as the ideas can be transferred to e.g. accommodation for foreign students or visiting researchers in Denmark.

Many American universities such as MIT, where 40 % of the undergraduate students are foreigners, deliberately attempt to make student life merge with private life. This is done, for instance, by integrating learning and group rooms at the residence halls, which are also used for teaching. This is a structure known in Denmark from the folk high schools, where learning and spare time also merge. MIT considers housing a good way of ensuring quick integration, which is particularly important to a researcher or student who is only visiting for a short time.

MIT also deliberately locates attractive researcher family accommodation in buildings where students live, in order to further contact in that way. This is supported by activities such as offers about communal eating. In practice, this means that the researcher and his/her family feel at home among the students, and that discussions continue after class in a more private setting. MIT has experienced better and quicker integration between visiting researchers and students as a result of the researcher being accommodated at residence halls on campus.

ETH Zürich is planning to construct a number of four-room housing options on campus, because they would like to have an attractive offer for students and foreign researchers with a family. They are financed by sponsors and will be rented out via a property company. The accommodation is deliberately designed as four-room units so that they can be used either for flat sharing with three to four students or as spacious researcher family units. This will also make them attractive to ordinary families, so that in times of recession the units might be let out to interested parties in the area.

In Denmark, a number of new, attractive foundation-funded student hostels have been built in Copenhagen, including the Bikuben and the Tietgen on the University of Copenhagen’s South Campus in the Ørestaden district. The offer here is attractive independent accommodation for young people, with the chance of interacting with peers. The interest in these housing units seems to be growing among students, and this probably means that this type of network accommodation, where you benefit from the resources of each other, is generally gaining popularity among Danish youth. However, these student hostels are built by donors without the involvement of the university or anybody else.

One of the challenges when offering accommodation to foreign visitors is to clarify who owns and runs the residences. In Denmark, the municipalities are generally under obligation to provide housing, but not particularly responsible for resolving this kind of housing issue. The universities can rent from private people, but experience – particularly from the capital – shows that typically, Danish universities cannot afford to rent appropriate accommodation close to campus, as the basic price here is typically too high. Another aspect is the relatively large amount of practical work that goes into finding accommodation on the private market – especially for visiting researchers who only visit for, say, a couple of months.

Strategy for sustainable campus planning and operation

The modern university has a strategy for its sustainable effort and it acts accordingly. The examples in this book show that sustainability far from being mere political correctness to the universities is an opportunity to save money in the long term. Danish universities must take the lead and ensure a sustainable strategy.

A good example of a successful organisation that has worked with this theme from an early stage is the ‘Harvard Green Initiative’, which was founded in 2000. The office has some 20 professional full-time employees who for a couple of years influence all building projects, for instance by making sure the environmentally correct American certification LEED is obtained and that the university’s users are trained.

Training may consist in creating a ‘peer-to-peer workshop’ for kitchen staff or students, in which they talk to each other and compete about who can save the most. Students from different academic subjects are recruited to be green ambassadors and get paid to turn up every two weeks to be taught concrete measures, which they can implement and pass on to their fellow students at the residence halls, e.g. saving water or turning off the light. Harvard has 10,000 resident students on campus, so the savings are significant.

This means that the people employed in the initiative work as a cross between practical caretakers who have water savers installed in the showers in the residence halls, and strategists who communicate the greater picture both downwards to the users and upwards to the management. All employees are self-financed in the sense that the university pays them as sustainability consultants who ensure environmental certification in reconstruction and new construction cases. It turns out that the additional expenditure for consultants and building costs are recovered through operational savings.

The Danish University and Property Agency is currently building its first CO2 neutral building at the University of Copenhagen’s North Campus. The Green Lighthouse will consume 22 kWh / m2, corresponding to 80 % less than prescribed by the Building Code. As a general rule, the Agency’s new strategy for the energy area establishes as a minimum to build in low energy class 1, which is 50 % below the Building Code.

In the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation’s essay competition about the physical framework for student environments at the country’s universities, students indicate that they find it a struggle ‘to be allowed’ to engage in sustainable work on campus. Both employees at Danish universities and the people behind the Harvard Green Initiative have also experienced how difficult it is to involve the students. Typically, they have very little understanding of the university’s organisation, and therefore it is difficult for them to act within it.

A considerable challenge remains in thinking sustainability into every step of the university’s operation and work. That being said, examples show that it is difficult to organise and systematise sustainable efforts at the universities. It is a laborious work with a lot of stages, and there are only very few models to follow. In an article in this book, the founder of Harvard Green Initiative, Leith Sharp, encourages universities to use sustainability as an opportunity to undergo a systemic transformation. She believes that they should move from being teaching and researching organisations to being learning organisations, too, which can professionally handle the transformation processes implied by sustainability.

World class?

How do we then create a world-class campus? Urbanity, sustainability, residences and the inclusive planning process each contributes and each expresses the same: It is all about using the physical framework and planning strategically and professionally to handle some of the challenges facing the universities.

This article is based on information from studies that can all be downloaded from the website of the Danish University and Property agency at www.ubst.dk /projekt Campus

NOTES

¹ Rector Finn Junge, theme meeting at the Danish University and Property Agency, June 2007

Campus cases

In this section, five campus cases combine to provide an idea of how international and Danish universities work with physical campus planning. These particular campus areas were chosen because they handle current challenges, which several other universities are also facing in their physical campus planning. ETH Zürich’s focus is urban integration, Harvard’s is sustainability, University of Copenhagen focuses on inclusion and art, Lancaster aims at the good student life, and MIT’s focus is on a planning process that furthers iconic architecture.

The five cases represent different campus typologies: An open campus, such as Lancaster University, which is surrounded by fields. A campus on the edge of the city, which strives to be integrated into the city, such as ETH. And finally, a campus that is integrated into the city, exemplified by Harvard University, University of Copenhagen and MIT. Common to all five cases is the fact that they deal with urbanity and the desire to open up and physically make the university visible in society. Their diffe-rent approaches result in their opening up in completely different ways. Some universities strive to integrate themselves into the city. In the case of others, the city is too far away, and therefore they create urbanity on the actual campus.

Each case consists of a campus analysis. This illustrates how the university is organised, how buildings and urban spaces as well as social and professional life work together, and finally, it describes the future strategies for the campus. The analysis is supplemented by amplifying interviews with people who are involved in the planning.

The cases may contribute as inspiration when universities, authorities and consultants create the campus areas of the future.

ETH Zürich

Urban integration

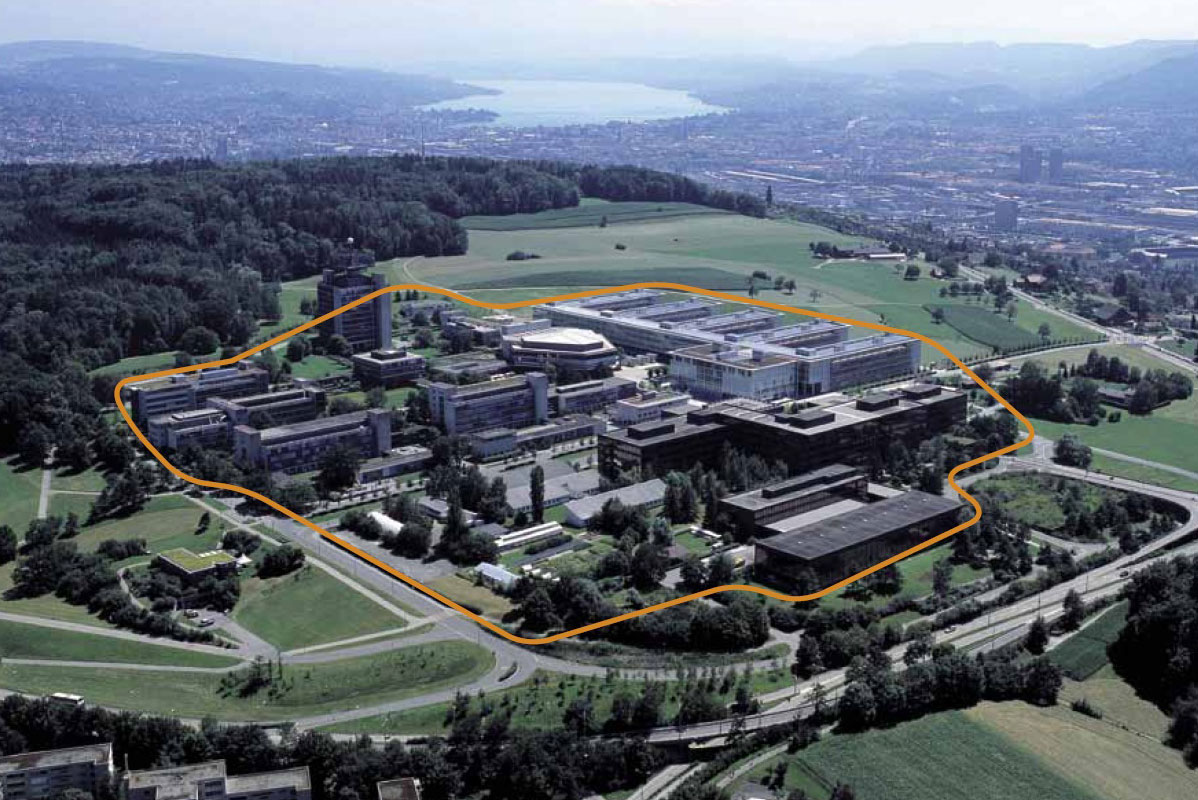

The ETH Hönggerberg (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich) campus was built after the Second World War on the outskirts of Zürich, 15 minutes’ drive by car from the city centre. The university wishes to turn the mono-functional Hönggerberg into a lively knowledge neighbourhood in Zürich. This development takes place within the framework of the Science City development project, which since 2003 has organised academic activities, communication and construction projects to open up the university to the surrounding world

| Hönggerberg, Zürich, Schweiz / | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1855; campus commenced in 1964 |

| Status | Federal university |

| Campus population | ETH Hönggerberg Campus: 5,500 people. In total 18,000 at ETH: 6,300 Bachelor’s degree students, 4,700 Master’s degree students, 3,000 PhD students and 4,000 technical and academic staff |

| Distance from the city | 7 km from the centre of Zürich (1.1 million inhabitants) |

| Subject areas | Engineering, Architecture, Humanities, Business, Science |

| Annual study fee | Approx. DKK 2,800 |

| Number of beds on campus | None |

Ownership and organisation

ETH is one of two federal technical universities in Switzerland as opposed to regional institutes of learning in the cantons. The federal Swiss government therefore owns the ETH buildings, and as a consequence, the university can only lease areas and rooms to parties with no academic interests such as private businesses, cafés and shops in the Hönggerberg campus area. ETH does not have the option of purchasing areas or buildings that can later be built on or leased. ETH is developing its university in close collaboration with the city of Zürich (construction permits and general political support), the canton of Zürich (public transport and educational framework) and the federal government (finances and overall strategy).

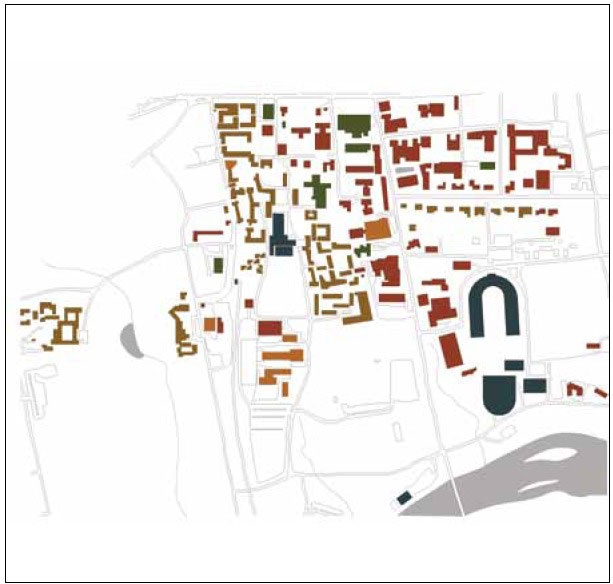

Urban spaces and buildings

ETH Hönggerberg was originally planned as a complex with large detached buildings of an almost industrial character intended exclusively for teaching and research. The university lies isolated in peaceful surroundings amongst fields and green woods.

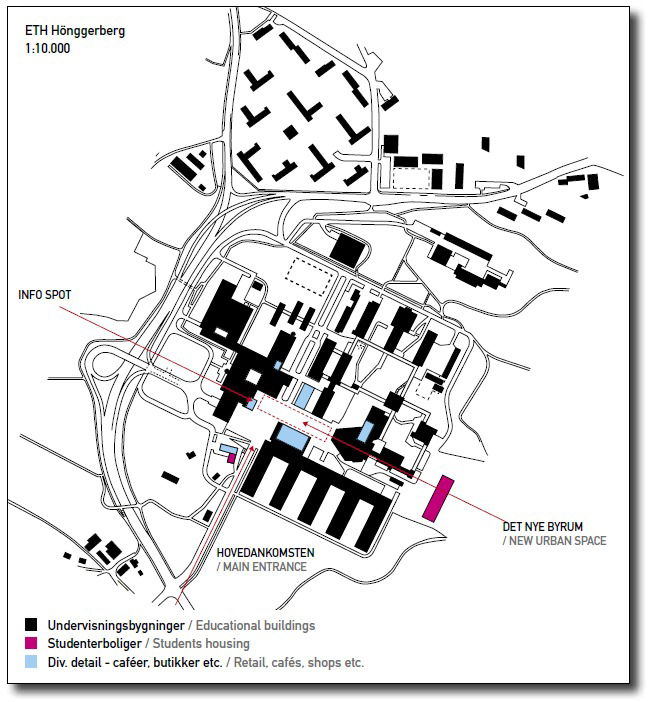

As part of the Science City project, an urban space competition was held in 2005. The winner was a flexible urban strategy proposing high-density construction to ensure urban qualities. The idea that private and public zones should overlap and create interaction constitutes another main component. In the past, ETH had kept the subject areas separate, e.g. engineers in one building and architects in another. The current strategy is to mix the subject areas in the different buildings to promote better understanding between the subjects.

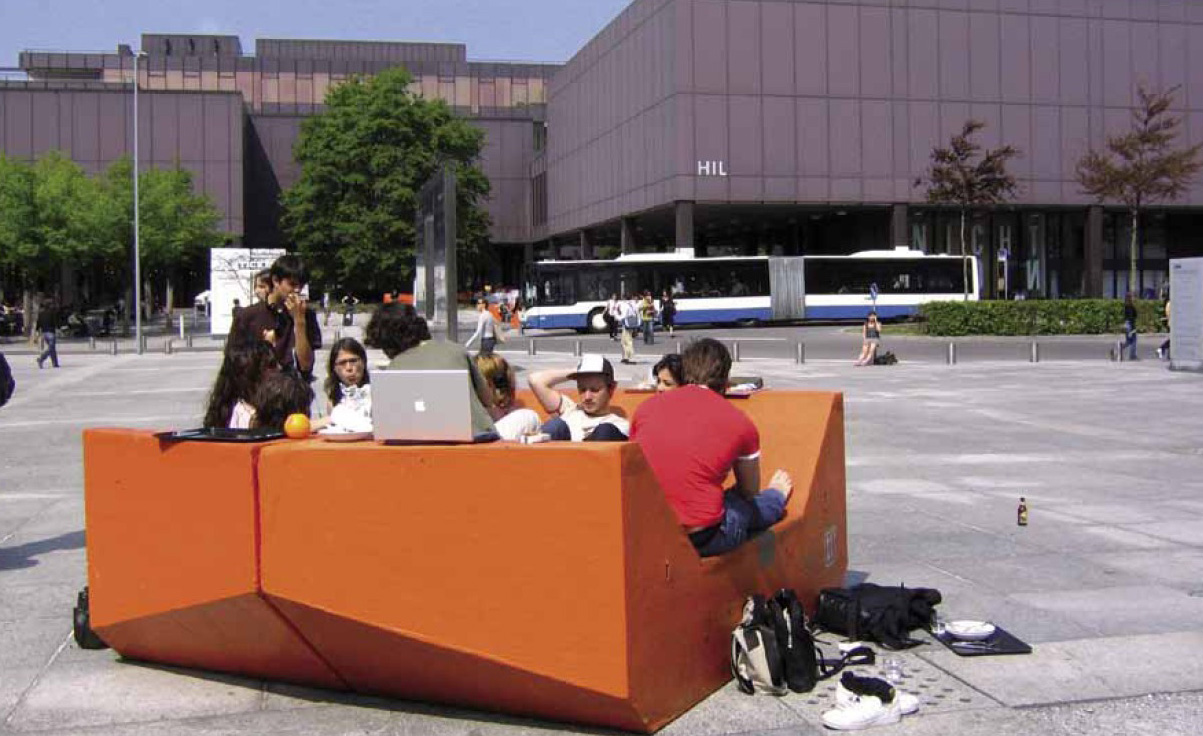

One of the most recent building projects has added a closed urban space to the campus in the form of a square. This square is now the central point of arrival and information and its urban character and local feel has made it very popular. The square is fitted out with large orange light-weight furniture that fills the spaces between the buildings. The furniture is a gesture that invites informal sojourns, playfulness and user influence.

Social and academic life

It is ETH’s intention that Hönggerberg Campus should be more than just a place of work and study, and therefore tours and lectures are planned that target user groups living in surrounding city areas. ETH communicates about research and current academic topics to user groups that normally do not have the opportunity to participate in such events during the day. Because of the growing number of visitors over the weekend, the university’s canteens are now open on weekends. This has sparked a positive spiral, as it has now also become more attractive for students to spend time at the university over the weekend.

Science City is also a learning project and the university includes the campus development in its curriculum and research projects. A research project at ETH about campus development, for instance, communicates knowledge about planning and sustainable campus development to other universities around the world.

A large international conference on sustainable campus development is held in April each year, which emphasises the central aspect of Science City: The intention is to make ETH Hönggerberg a sustainable urban area – and at the same time efforts are being made to use Science City as a starting point for the creation of an international sustainable network. Disseminating and initiating knowledge becomes an active component of the university profile.

Future strategy

The Science City project is to ensure that Hönggerberg becomes an ‘academic city area’ with more than just academic functions. The Science City project is a platform that the university uses to create a dialogue with authorities, inhabitants and interest groups about the development of the area, and the platform is also used to create the framework for a master plan, traffic, sustainability, financing, communication and maintenance.